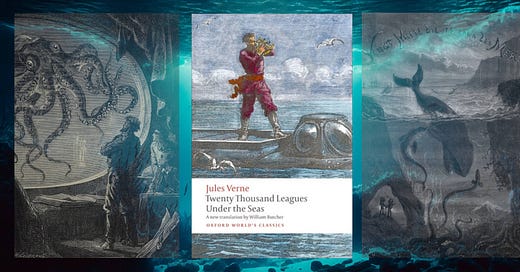

1870: Captain Nemo

Jules Verne brings the antihero out of civilisation - and gives him his own domain beneath the waves!

“I am not what you call a civilised man! I have done with society entirely, for reasons which I alone have the right of appreciating. I do not, therefore, obey its laws, and I desire you never to allude to them before me again!” - Jules Verne, 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas

In my childhood, I thought Jules Verne had erred in suggesting we could descend tens of thousands of miles under the sea – the oceans simply aren’t that deep! But of course, the title isn’t about depth but about distance. As with all of Verne’s ‘Voyages Extraordinaires’, we are taken on a journey, in this case, a guided tour beneath our planet’s oceans. The novel is exceedingly precise and well researched - we are given the exact latitude and longitude of incidents in this submarine adventure, and Verne painstakingly recounts lists of the actual aquatic life to be found in each place visited, as compiled by his protagonist (a marine biologist), with only minor errors. It is hard to imagine a writer today going to such great lengths on such trivialities - yet for Verne, this was a mere stylistic flourish.

The core of 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas is its brooding antihero Captain Nemo, whose name is Latin for ‘no-one’. Verne’s inspirations included the fantastical writings of Edgar Allen Poe, whose proud, ambitious, and melancholy conqueror Tamerlane was expressly inspired by Lord Byron’s dramatic poetry. The torch that gave us the fire of the antihero passes directly from Milton, to Byron, to Poe, to Verne. But in Nemo, Verne gives us something entirely new and remarkable. The Captain of the incredible Nautilus is not merely a hero without heroic traits, he sets himself outside ‘civilised’ society. In a line that seems to echo Nietzsche’s ‘overman’ Nemo declares “The earth does not want new continents, but new men.”

Verne vision for Captain Nemo was inspired by the brutality of the Russian Empire in Poland. The January Uprising of 1863-4 saw the Polish people attempt insurrection against the rule of Tsar Alexander II - who viciously supressed the rebels and brutally punished its ringleaders. Verne imagined a Polish nobleman whose family had been slain by the forces of the Tsar. From within his technologically advanced submersible, Captain Nemo wages a guerrilla war against Russian ships, enacting vengeance against the Empire that took everything he loved away from him.

However, his publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, was wary of publishing a book so directly critical of Russia. Not only were France and Russia allies at this point in time, but Hetzel knew that Verne’s novels had a strong readership in the Russian cities, and didn’t want to lose the revenue the book would make there. Verne protested, but eventually acquiesced by keeping his intended backstory within his own head, and omitting from the text anything specific about Nemo’s origins. “Since I cannot explain his hatred, I will keep silent about the reasons for it, as well as my character’s past, his nationality, and, if necessary, I will change the novel’s resolution.” (He later invented a different backstory for Nemo: but not in this novel.)

Verne was disinterested in political arguments. In his concession letter to Hetzel he wrote “I do not want to engage in politics, which I do not understand at all and which has nothing to do with any of this.” His interest was exploring this passionate character and his extraordinary home (and weapon...) the Nautilus. Verne considered all of his ‘scientific romances’, to lie on the brink of the realistic. This was important to him, and formed his key criticism against H.G. Wells, who established the broader mechanism of science fiction (i.e. make up cool stuff). Verne, however, was a novelist first and a speculator second. Character and story were his guiding lights.

Captain Nemo represents a rejection of the supposedly civilised society of ‘land’, and Nemo himself has vowed never to set foot upon the lands of nations ever again. Instead, he and his intensely loyal crew live underwater, speak their own language, and bury their dead beneath the waves. Although he flies a black flag when claiming the continent of Antarctica, he is not an anarchist but rather sees himself as his own power, unfettered by the laws of mankind and pursuing his scientific researches wherever they lead him. This is an antihero that has a nobility of purpose, but is unbound by conventional ethics. Further along this path lie the great antiheroes of the twentieth century.

Never read Verne. Maybe I'll get round to his work some day.