“All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current concepts, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently the first condition of progress is the removal of censorships.” - George Bernard Shaw

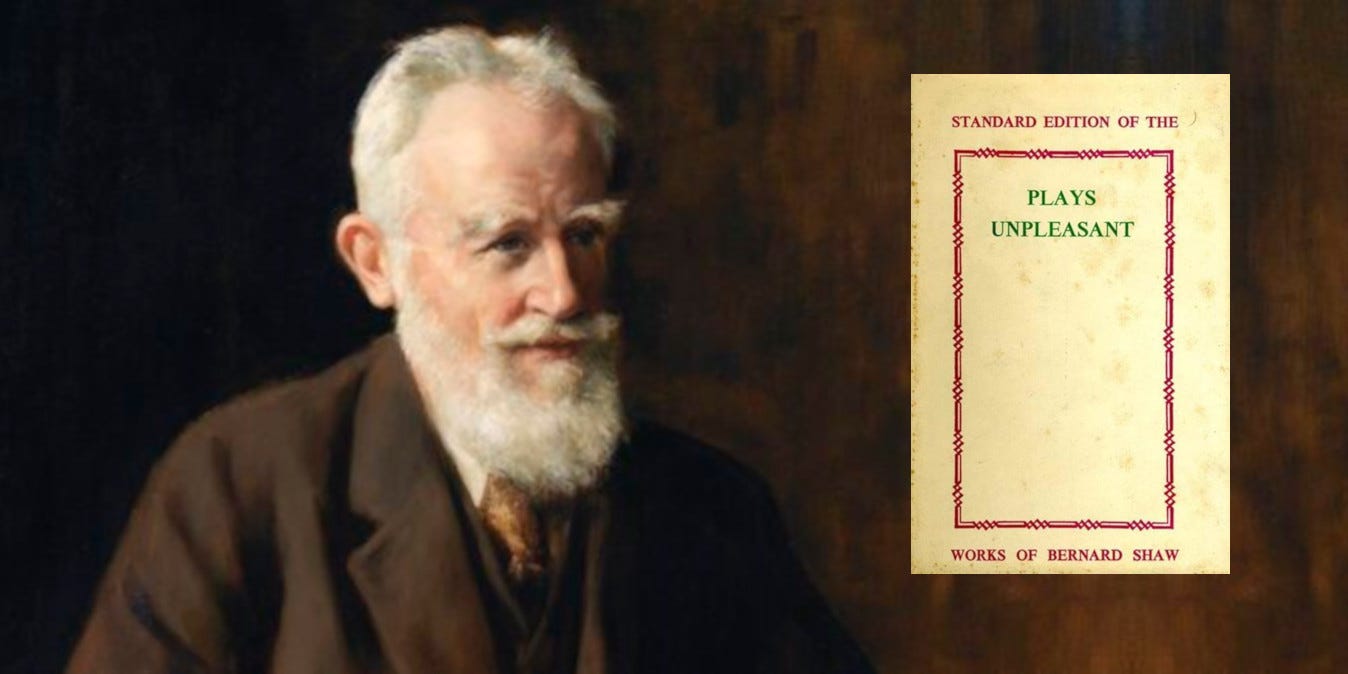

In 1898, Dublin-born playwright George Bernard Shaw finished writing the last of his ‘Plays Unpleasant’, Mrs Warren’s Profession. Victorian theatre was largely about entertaining audiences, but Shaw had other purposes in writing this loosely construed ‘trilogy’. Each one, while comedic, serves to illuminate a concealed aspect of late-nineteenth century society. Shaw speared youthful idealism, exposed grim economic realities, and challenged the double standards imposed upon the women of his time. Although all three plays have come to be regarded as classics (and are still performed today), Shaw had great difficulties getting them staged in his own time.

Since the middle of the seventeenth century, the term ‘the Censorship’ referred to a position, the role of a censor, which is to say a judge of public morals. In the British Empire of Shaw’s time, the Censorship belonged to the Lord Chamberlain, a senior figure in the royal household, who was charged under the Licensing Act of 1737 with distinguishing ‘legitimate theatre’ from ‘illegitimate theatre’. Shaw faced enormous opposition from the Censorship of the Lord Chamberlain, and his ‘Plays Unpleasant’ were only performed by taking advantage of a loophole, whereby the law applied solely to public performances, and not to private members clubs. This was how Mrs Warren’s Profession was finally performed in 1902, eight years after it was written.

In 1905, Shaw added an introduction to the book of the play, entitled “The Author’s Apology”. As you might guess, this was Shaw’s ‘sorry not sorry’ condemnation of the treatment of the play by critics at the time, and especially his excoriation of the Censorship. Oddly, he suggested that this institution was popular among the people of Great Britain, and made it clear that the problem was not about who held the office. Indeed, he stated that if a distinguished scholar of poetry were to take the position, “the new and enlarged filter will still exclude original and epoch-making work, whilst passing conventional, old-fashioned, and vulgar work without question.”

Thus Shaw reaches the conclusion quoted above - that the first condition of progress is the elimination of all censorship. In some respects, this is a strange claim - the previous century had already shown considerable signs of progress, despite the continuation of the practices of censors and examiners. Yet Shaw’s argument has teeth: if we cannot criticise what is wrong with the current state of affairs, we cannot hope to solve problems. Even if one does not hold to an ideal of progress (as Shaw did), this principled opposition to giving anyone the power to choose what others cannot read, watch, or hear remains an essential element of the collective equality that must animate any legitimate democracy.

Yet the contrast between Shaw’s principles and contemporary political agitation is stark. A significant number of those who consider themselves progressive defenders of democracy now passionately advocate for censorship of free speech. Activists demand punishments for nebulously defined ‘hate speech’. Reporters selectively suppress stories according to which political candidate they benefit. Academics demand the prevention of scientific discourse concerning the impact of atmospheric gases. Government officials in the US and Europe pressure social media companies to defend pharmaceutical corporations by concealing evidence of both fraud and unprecedented degrees of harmful side effects. These anti-democratic abominations could never be associated with authentic ‘progress’. This is pure and unadulterated regression, the voiding of liberty and the defence of the powerful from justified and necessary critique.

The great irony of moralism - which is rarely grounded upon legitimate ethical concerns - is that by making a demon out of those who offend the sensibilities of each outraged puritan, severe problems escape necessary redress. Such was the theme of Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, which indicts Victorian double standards regarding prostitution that had been deemed despicable in the context of each and every practitioner, yet was still quietly defended as a ‘necessary’ social evil. Today, progressive double standards abound around the issue of censorship, as puritanical culture warriors show no interest in a democracy secured by collective equality, and gleefully tilt the scales towards whatever causes they happen to prefer. The establishment has changed hands, and now the very name ‘progressive’ marks the same hypocrisy Shaw attacked in the thinly-justified moralism of his own time.

Chris,

You address the complexity of human communication on a community basis without getting to the basis, purpose or objectives for the problems you cite as censorship. Whatever issive or ism which you identify as the primary offender actually spans the full spectrum of human engagements whether they be characterized as Left-Right; Conservative-Progressive; Secular-Religious; Scientific-Religious; ....

You might find of interest in todays Washington Post "Why Jack Dorsey gave up on Bluesky" (https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/05/14/why-jack-dorsey-gave-up-bluesky/)

"What both Dorsey and Musk seem to overlook is that it isn’t just big corporate brands that dislike social networks riddled with bigotry and extremism. Most ordinary users don’t want that stuff either."

"“No matter what, even in a decentralized system, it will be impossible to do moderation well, and people are still going to hunt down someone to blame,” Masnick wrote. “That is human nature.”

When does Moderation of Communication become censorship?

Insightful piece here, Chris. Great concluding sentence! Hard to say if the eighteenth century was marked by true progress considering the fallout of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars and American Civil War that ensued. The rise of the bourgeoisie is certain and with it a kind of secular ethic. The power of the clergy gave way to the powers of industry and the sciences that fuelled it, but really it's the same old story. Those who take power from the abusers of power really just want to be the abusers of power themselves and prove as much as soon as they're installed.