The Communion of Theatre

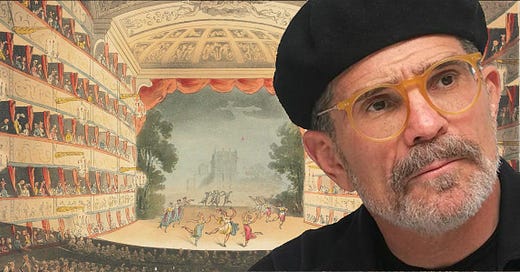

Playwright David Mamet's unique perspective on the rituals of theatre and film

“When you come into the theatre, you have to be willing to say, ‘We’re all here to undergo a communion, to find out what the hell is going on in this world.’ If you’re not willing to say that, what you get is entertainment instead of art, and poor entertainment at that.” - David Mamet

As much as I love the theatre, I confess to have spent far more of my time in the cinema than in the shade of the proscenium arch. Partly, this is practical: theatre tickets are expensive, more suitable for a special occasion than a weekly venture. But partly this is down to something else entirely: the fact that much of what is out there on the stage is, as David Mamet accuses, entertainment. If I am to be entertained I would rather do it with a movie, which indulges in its spectacle with an unabashed glee. Yet even with the merely entertaining there is ritual entailed, one found in both watching a film in the ‘movie theatre’ and watching a play upon the stage... one we neither acknowledge nor appreciate.

The two art-forms share in common the arrangement of the audience in banked rows whose gaze is focussed upon one place - the stage or the screen. The ritualistic element in this experience is lost on those of us who have been enacting it our entire life, as we have been successfully trained in its performance and can no longer question it. Yet the contrast is as clear as day when you compare what happens when a family sit around a television to chat over a film versus a trip to either kind of theatre. It is not merely the politeness of not speaking while the show proceeds, it is the demand of our attention such that it requires our complete attention. Conducting this rite we are immersed in the imaginings - that this painting represents a certain place, that these people truly are who they are pretending to be.

Mamet goes further than merely picking out this ritual of imagination: he suggests that when the theatre fulfils its calling as an art form the audience is called into communion with the theatre company. You could read this term without its religious overtones, certainly, as simply saying that thoughts and feelings are being exchanged between those who watch and those who perform. I suspect, however, as someone with a life-long relationship with Catholic-leaning New York (even if he lives in nearby New England) that this choice of word is intended to evoke the deeper mystical aspects of the rite of holy communion. Here too an act of imagination places the devotee into symbolic contact with the eternal mystery that Christians name ‘God’. Mamet needs such an analogy to defend the cleaving of (sacred) art from (profane) entertainment.

All attempts to erect fences at the boundary of art may seem futile... certainly, we never reach any agreement about where these fences should stand. Yet the borders between nations are just as imaginary, and few would dare to deny their lived reality, enforced as they are with such violence. Mamet’s distinction for art against entertainment successfully grasps why we have a name, ‘art’, for the most laudable creative expressions. The idea of communion between the artists and their audience strikes at the heart of the artistic experience. What’s more, it recognises that whether something is or is not ‘art’ isn’t a question of ascribed properties but a matter of attitude.

For the theatre, and for some films as well, the ritual imagining conveys a snapshot of the world outside, one that may deliver unto our understanding what otherwise might elude our grasp. This is the essence of artistic achievement, and the reason Shakespeare’s plays are still performed today despite being written nearly half a millennia ago. They capture something eternal about the human condition that remains as true today as it did during Elizabethan times, when the theatrical ritual was ironically closer to the family around the TV than the monastic rite it is today. Art speaks to us across time and space, it permits a communion that may not be holy, but it approaches the sacred.

Indeed. Strip away all the myth; take a totally objective, observational view – the mystery remains!

Well stated, Chris. Interesting to find the same "communion" theme in McGrogan's piece this morning. Something's afoot in the collective spirit.