No Reality without Representation

The challenge from Bruno Latour: give up our addiction to universal categories and instead co-operate on building a shared political home

“Where does ‘external nature’ now lie? It is right here: carefully naturalised, that is, socialised right inside the expanding collective. It is time to house it finally in a civil way by building it a definitive dwelling place and offering it not the simple slogan of the early democracies – ‘No taxation without representation’ – but a riskier and more ambitious slogan – ‘No reality without representation!’ ”

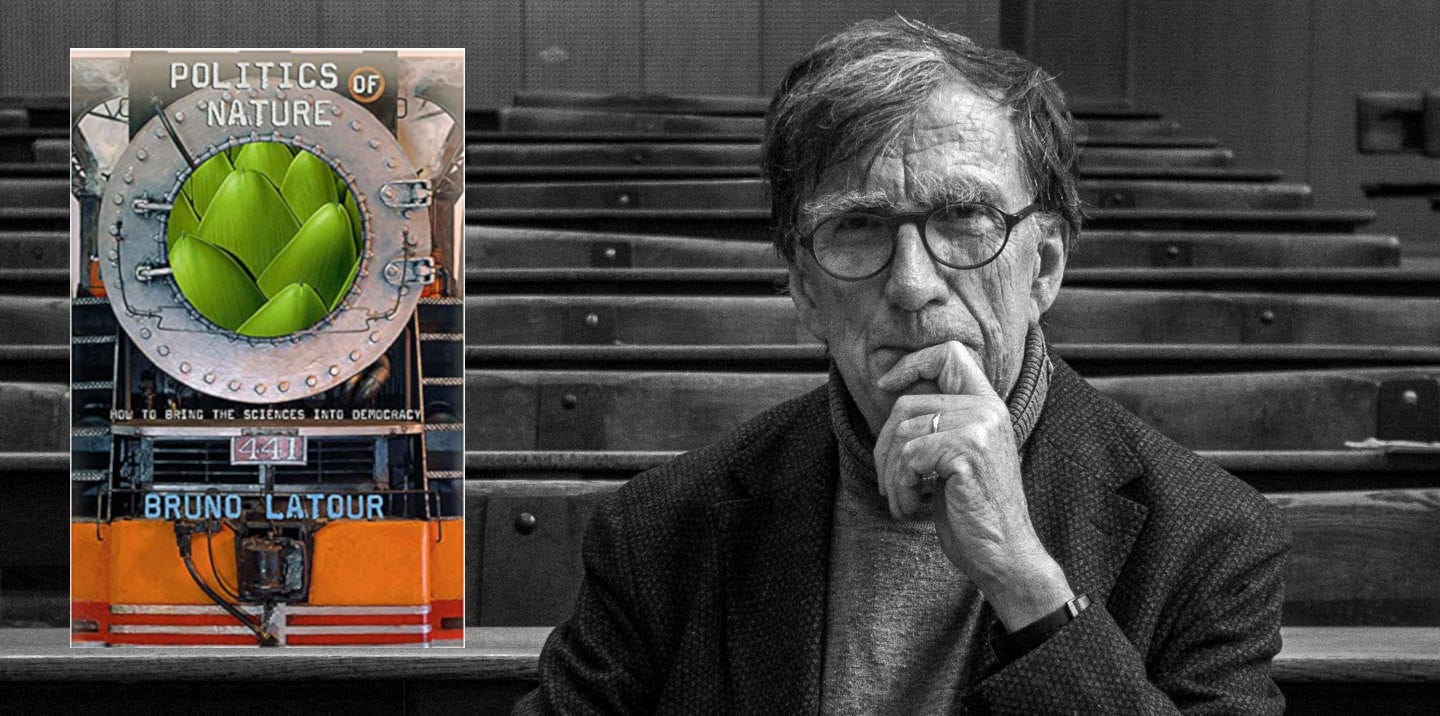

- Bruno Latour, Politics of Nature

The late Bruno Latour was France’s most popular philosopher. This is quite a statement - popular philosopher! It is practically a contradiction in terms, for philosophers are seldom welcome anywhere, although there is a thriving industry for secular apologetics, especially when it defends the deployment of some new technology for scurrilous purposes. Yet Latour was indeed a popular figure in France, having earned notoriety for his brilliant sociological studies of the sciences. Only later did he ‘come out’ (his words!) as a philosopher.

In Politics of Nature, Latour explored a unique project. Despite its brilliance, it is among the less popular of his excellent books, and the first and only time since Immanuel Kant’s Enlightenment philosophy that someone has attempted to rebuild the conceptual foundations of a functioning collective on the scale of a nation. Kant, indeed, seems to have been part of Latour’s inspiration for this project, which probably explains why it resonated so poorly with others and so greatly with me (a Kantian fanboy, considered a heretic by the ‘big names in Kant’).

Latour’s philosophy is grounded to a great degree on a challenge to the monolithic concept of ‘nature’. To his amazement, ‘nature’ maintained its appeal as a supposedly unchallengeable universal category, quite unlike that other long-standing universal, ‘Man’, which was quietly dissolved from polite conversation. By maintaining a mythic image of ‘nature’, ‘culture’ was permitted to fill up the space of everything else, with ‘nature’ taking up the reigns of Kant’s objective and ‘culture’ his subjective, in a scheme that everybody accepts, but that Kant - as Latour - would have roundly repudiated.

Around this idol of ‘nature’ can be found so many of the problems concerning scientific discourse. In assuming that the wonderful mathematical precision of the equations of physics are the template by which science is legitimated, a tremendous soft focus was adopted in which we ceased to examine what the sciences actually do. Latour’s friend and inspiration, Isabelle Stengers, helped awaken him to a greater appreciation of the complexities of scientific discourse, and Latour in turn saw how evoking ‘nature’ was all that was left to those claiming the authority of science, since they could no longer turn to God to attempt to circumvent debates. If Latour did not anticipate the coming censorship regime bullying towards a singular version of scientific ‘fact’, he still exposed the roots of this appalling travesty.

Latour’s vision is of a “politics without nature” - that is, without the power to come in and say ‘these people (the legitimate scientists) speak for nature, and you may not argue with them’. As he suggests, if absolute power corrupts absolutely then giving someone the power to define the terms of our common world by claiming the authority of nature was inevitably going to lead to corruption. Latour, in fact, did not even live long enough to see just how dismal this would become! His call for peace - to an end to war both within the sciences, and between them and other worlds - rested on recognising the dignity of everyone who comes together to form a common world, and who must learn to doubt if this common world is to be anything but an empire in disguise.

His call for an “experimental metaphysics” as the basis for a new kind of conceptual parliament remains as insightful and relevant as it did nearly two decades ago. How different it could have been if the political left had taken up this incredible challenge! Alas, Latour came out as a philosopher at a time when most philosophers had already been tainted by the idolatrous power of ‘nature’, and there was almost nobody left to pursue his project (although I have attempted to do so). His vision for a parliament that transcends the substitution of scientists for priests remains as vital and innovative as when he first suggested it. It is summed up perfectly in a revolutionary demand that I have strived for longer than I can recall: “No reality without representation.”

Chris, it would have been helpful if you provided a definition of what Latour meant by "external nature" which I take to mean discoverable physical reality of which humans are a part.

I asked ChatGPT:

Bruno Latour, a French philosopher, sociologist, and anthropologist, is known for his work in the fields of science and technology studies (STS) and his influential ideas on the relationship between humans and the natural world. Latour's perspective on the concept of "external nature" is deeply intertwined with his broader philosophical and sociological framework, which challenges traditional distinctions between nature and society. His work often blurs the boundaries between what is considered natural and what is considered social or human-made.

Latour argues that the traditional notion of "external nature" as something separate from human society is a misleading and problematic concept. He contends that humans are not passive observers of an external, pre-existing natural world but active participants in shaping and constructing what we understand as nature. In his view, nature is not something "out there" that is independent of human influence but is, instead, a product of human interactions, beliefs, and practices.

Latour's perspective is often associated with his concept of "hybridity" or "hybrid collectives." He suggests that humans and non-human entities (such as technology, animals, and natural elements) are interwoven in complex networks or collectives. These networks include both human and non-human actors, and they shape our understanding of reality.

In essence, Latour challenges the idea that there is a clear and distinct boundary between the natural world and human society. He argues that we should approach the study of nature and society as intertwined and co-constitutive, rather than as separate realms. This perspective has had a significant impact on fields such as environmental studies, sociology, and anthropology, as it encourages a more holistic and relational approach to understanding the complex interactions between humans and the environment.