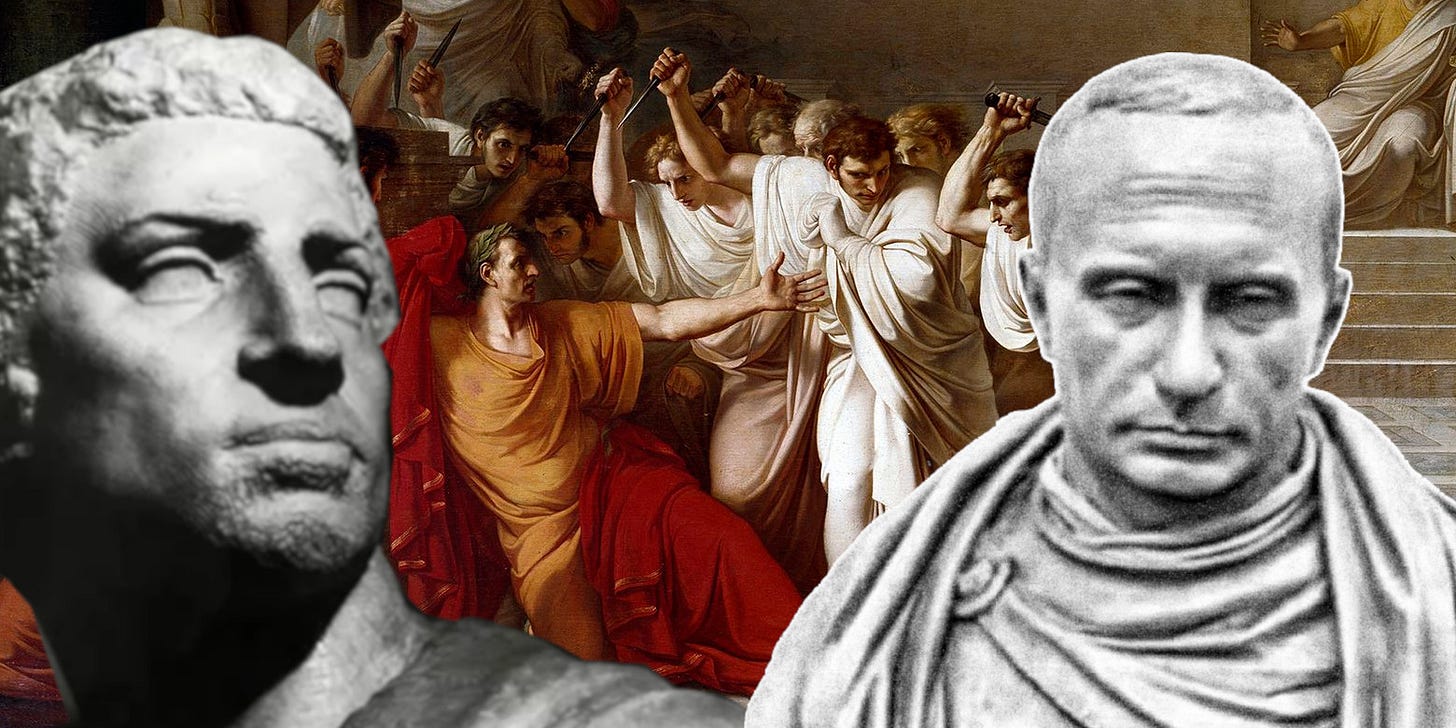

No Brutus for Putin

Shakespeare's dramatisation of the assassination of Julius Caesar, and why no such bitter betrayal awaits Vladimir Putin

“There is a tide in the affairs of men.”

- Brutus (The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3)

Contemporary authoritarian Russia has as its figurehead Vladimir Putin, a far more complex person than we in the West are typically willing to acknowledge. Suppression of the press, violence and lawfare against the opposition... we may pray that our own nations don’t end up where Russia is now, but Putin enjoys massive popular support at home. We are discouraged from admitting it, but if Russia suddenly decided to hold free and open elections, the overwhelming likelihood would be Putin remaining in power. Outside of Russia, some dream of what is euphemistic called ‘regime change’. They desire a Shakespearean Brutus close enough to Putin who would be able to remove him from power. But this can never be.

A striking aspect of the eternal appeal of Shakespearean tragedy is also one of the most surprising, given the circumstances of contemporary life. Shakespeare writes all his characters from a background rooted in virtue ethics, which is to say, with an understanding of the good that is framed around the elements of people’s character. The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, for instance, is not so much about its titular leader, who is killed nearly exactly in the middle of the play. It is far more about the honourable Brutus being drawn into supporting the nefarious assassination, his conflicting feelings about this, and his eventual downfall in the aftermath as a direct consequence.

Today, we not only do not practice virtue ethics outside of certain minority communities, we have lost the capacity to think in terms of virtue entirely. We will certainly pour scorn upon people for their supposed failings - and both Putin and Donald Trump have been remorselessly judged by the commentariat in this regard. But this is a long way from the core of virtue ethics, which is to cultivate aspects of our own personalities that promote human flourishing and the common good. The usurpation of virtue ethics by mathematical simulacra of morality from the nineteenth century onwards fools us into thinking all that matters are outcomes. Yet without virtue, even the most obsessive attempt to control the future will not prevent catastrophe, as indeed we have witnessed first-hand in recent years.

The engine of the drama in Julius Caesar is that Brutus is an honourable man, and as such he is troubled by the rising tide of Caesar’s power and ambition. Brutus is afraid of any single person ascending into a tyrannical reign, believing that discourse in the senate is a requirement for wise government and that this will not survive if Caesar becomes a dictatorial leader, much less ‘dictator for life’. But Caesar is enormously popular with the Roman people. In the play, Mark Anthony offers Caesar the crown three times, with the enthusiastic support of the citizens. Caesar, however, appreciates that Romans are adverse to kings and shrewdly declines. Yet as he continues aggregating authority, a coalition of conspirators eventually assassinates him, all striking together so that none can say for certain who landed the fatal blow. Even the circumstances of this terrible deed are draped in echoes of virtue!

Historically, less than twenty years after Julius Caesar’s death, his adopted son Augustus transitioned the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire, and this is also part of the wider context of Shakespeare’s tragedy. Those outside the cheap seats would certainly have known that Brutus’ attempt to uphold republican virtue was ultimately doomed. But the entire audience also knew that having committed murder, whether of a political figure or an individual, Brutus’ idealism and adherence to principle would not excuse him from the consequences of his actions. These consequences, however, are understood as flowing from his character and not from calculus.

The desire of the western political class to remove Putin from office falls flat because despite the direct parallels between Julius Caesar and Vladimir Putin, there is no Brutus for Putin - and this in two senses. On the one hand, the ruthless efficiency of his training as a KGB case officer provided Putin skills in realpolitik that help prevent anyone amassing the influence required to overthrow him. But on the other, anyone in Putin’s inner circle will also (as with any western political leader you’d care to mention) lack honour. The ultimate cost of abandoning virtue ethics has been far greater than anyone could have calculated.

Nice. We end up considering virtue ethics.

“there is no Brutus for Putin” in two senses: (1) having more room to maneuver than Caesar, Putin has ensured that a no inner cabal with sufficient influence can arise, and (2) those in Putin’s inner circle have been thoroughly morally compromised [a reasonable guess - how certain can we be?].

“any western political leader you’d care to mention” [lacks honor]

Really? There are a lot of western political leaders.

“The ultimate cost of abandoning virtue ethics has been far greater than anyone could have calculated.”

As I understand it, virtue ethics is just about individual action. But clearly culture has a lot to do with the prevalence of virtue ethics in a society. I take it that you are claiming that cultures around the world have backed off inculcating virtue ethics in their individuals.

[Note to self: review Chaos Ethics by Chris Bateman]

"Suppression of the press, violence and lawfare against the opposition... we may pray that our own nations don’t end up where Russia is now..." Any irony here? I guess we're still not quite as bad off as Russia. But I think we're inching our way there.