Digital Souls

My final exchange with Mary Midgley and the solution to the problem of free will

“Thus the reason why people find it so hard to think about Free Will is that they haven’t yet begun to wonder how to connect life’s two aspects - the unpredictable flow of personal experience on the one hand and the fixed, deterministic system of calculation that appears on our clocks, calendars and such machines on the other.” - Mary Midgley

When she was 99, Mary Midgley wrote her last book, What Is Philosophy For? I was honoured to receive the author manuscript as she was sending it off to the publisher, and humbled by the clarity and scope of this final statement of her work. Six months before her passing, we were engaged in a lively debate about the book’s themes. I was working on my book The Virtuous Cyborg, and she told me she flatly didn’t believe in cyborgs. I knew what she meant. But I explained to her that I’d simply named any combination of a human and a machine as ‘cyborg’ , a means (I hoped) of drawing people into thinking about technology more critically and less triumphantly. This was to be our final exchange.

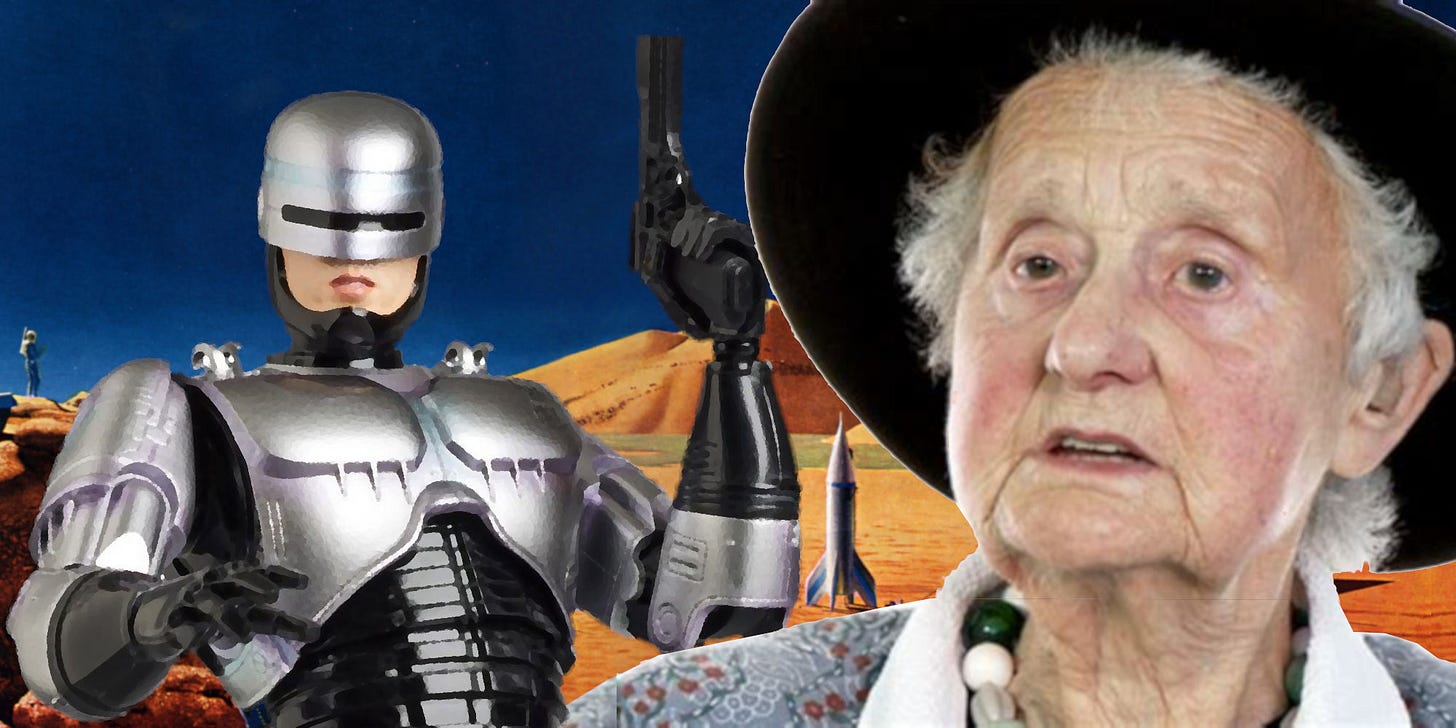

Midgley and I shared a fascination for the power of mythos to shape or warp our experiences. Hence her enthusiastic endorsement of my book The Mythology of Evolution, which explores the mythic dimensions of a scientific domain that’s far more intricate than either its popularisers or critics allow. Science fiction, as I say in that book, is a form of fantasy, one in which the mythos of the present (rockets, robots, regeneration) provides the raw inspiration, rather than the mythos of ages past (dungeons, dragons, divination). Midgley saw this as a consequence of two centuries spent transitioning from trust in God to trust in machines. Rather than expecting the Rapture to take them away from the Earth, tech-believers wish for the Singularity so that they might ascend to digital heaven. Both ancient prophets and science fiction writers promise glory to come, the latter sometimes leaning on uniquely contemporary metaphysical confusions.

The idea of digital souls, the uploading of our consciousness into machines, is the final revenge of Descartes’ split into matter and mind. Far from escaping this division, present-day dogma pretends the mind is mere illusion, while matter is the sole ‘real’ stuff. This empowers visions of a make-believe mechanical metamorphosis. But matter, as Midgley shrewdly observed, is not inert, and hasn’t been thought as such for some time. The purpose of staking so much faith in the inanimate is to avoid the inherent complexities of our mental worlds, which have always resisted the dissecting scalpel of Victorian-style sciences. It is an important yet under-discussed side effect of this metaphysical conviction that while religious redemption requires us to strive for the good, technological salvation expects nothing from us but to wait for the magic to happen. Hope, of a kind, even for the wicked and lazy!

Midgley’s final analysis of the problem of free will is bound up in her defence of philosophy. We have always struggled to understand volition because we haven’t even begun to wonder about how to connect the splendid chaos of our personal experiences with the reliable determinism of clocks, whether mechanical or digital. Neither of these models is sufficient on its own: they are two different ways of imagining the process of life and existence. Two different languages, serving different purposes. “Lightning and thunder are not really separate items; they are two partial representations of a single electric discharge.” We have avoided engaging with this - the true ‘problem’ of free will - because the materialistic credo of our time has always been framed negatively. Its practitioners have sought to deny us sufficient headroom to think about minds, thus repudiating any talk of souls.

But this conceptual manoeuvre is an empty gesture, for even when the extraordinary beauty and horror of our lived experiences are stripped down to supposedly inert matter in an act of foolhardy scientistic exorcism, we never actually lose our faith in the soul. We simply adapt it to the machine mythos. Rather than immortal souls destined for the next life, we become software inhabiting wetware ‘meat’ that shall soon upload its digital soul into undying hardware. Our future, who art in Robocop, hollow be thy game.

The problem of free will doesn’t persist because it is insoluble. It endures because we are too stubborn to practice the art of philosophy, rejecting naïve simplifications for the subtler practices that strive to reconcile the complexities of existence.

Midgley is always of interest. I wonder what you mean by "We have avoided engaging with this - the true ‘problem’ of free will - because the materialistic credo of our time has always been framed negatively." In what sense, "negatively"?

Review: What is Philosophy For? by Mary Midgley

https://philosophynow.org/issues/144/What_is_Philosophy_For_by_Mary_Midgley

How do your Cyborgs relate to

The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology Book by Ray Kurzweil