Bread and Thoughts

Does the question of free will actually matter? Moorcock's challenge to H.G. Wells provides a clue

“Man can live by bread alone when all his energies are devoted to attaining that bread, but once his mind is clear, once he has ceased to labour through all his waking hours to find food, then he begins to think.” - Michael Moorcock, The Land Leviathan

Beyond the deep philosophical questions of free will lies the pragmatic question of its exercise. For it is unavoidable that anyone with the time to engage in metaphysical debate about what this freedom means is already removed from the struggle for daily existence that Michael Moorcock refers to in the quote above. Referencing the first temptation of Jesus in the wilderness, the time-wrecked Edwardian soldier Oswald Bastable (Moorcock’s narrator in The Land Leviathan), recounts the tale of the doomed alternative history he has found himself in. He encounters a total unravelling of civilisation at the end of the Victorian age resulting from the invention of machines intended to liberate humanity from hunger and toil.

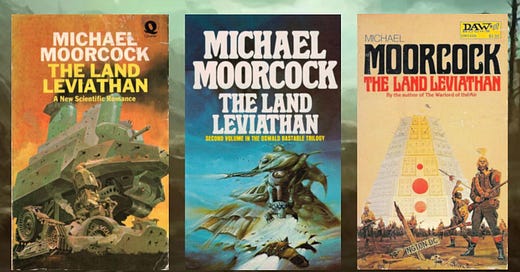

The three ‘scientific romances’ in this trilogy were inspired by Moorcock’s admiration for H.G. Wells, but the primary spur for this novel is Wells’ short story “The Land Ironclads”, which is credited for predicting the creation of tanks. Wells recounts a war correspondent reporting on the crushing defeat of rifle-armed soldiery by a force of “civilised men” riding an enormous mechanised vehicle. Moorcock, far more sceptical of technology than Wells, takes this tale and inverts its overly-simplistic message. Wells imagined his new war technology allowing civilised “townsmen” to overcome the brute force of traditional warfare. Moorcock has the knowledge of two World Wars to inform him of what actually happens when humanity’s remorseless advancement of tools collides with our impulse for bloody conflict...

In the alternative history of The Land Leviathan, a young Chilean genius in the 1870s invents new power systems, thus creating a swathe of new inventions. At fifteen, he turns his attention to war machines (“he was still a boy and was fascinated, as boys are, with such things”), inventing underwater boats, airships, mobile cannons, and fearsome ‘land ironclads’ of the kind imagined by Wells. As his social conscience develops, he foreswears weaponry, working instead upon “machines which would irrigate deserts, tame forests, and turn the whole world into an infinitely rich garden”, believing that the existence of hunger was the “the well-spring of most human strife.”

But this backfires. As the quote above attests, removing the necessity of working to survive merely gives the impoverished room to think, leading to envy of “the landowners, the industrialists, the politicians and the ruling classes”. By 1900, every nation is beset with strife, worsened by trade embargoes and “crippling and unnecessarily unfair tariff restrictions”, while the rulers of nations see themselves threatened domestically by the younger generation demanding “social justice” and by neighbouring countries, all of whom are building up huge armies of war machines in the hope of controlling “dissident populations”. War is sparked in Europe, and nations everywhere become swiftly devastated. When the fuel is all used up, the war machines become useless, and warfare returns to infantry and cavalry, even though “there was hardly anyone knew how to fight like that - and precious few people left to do it.”

Such is merely the setup to The Land Leviathan, a post-apocalyptic planet ruined by the invention of great technological wonders sparking the World Wars half a century earlier, and rendering them even worse than our own Great War and its successor. All these tales of Oswald Bastable’s steampunk adventures in alternate history circle around the same themes: the madness of war and the relationship between racism and empire. But this trilogy is not merely a scornful warning about Wells’ technological optimism. Their recurring motifs are animated by Moorcock’s insights as the last of the existentialist philosophers.

For Moorcock, free will is a tiny force, one barely able to render an impact on the flow of events. Bastable is simply swept along by the inexorable calamities he is caught up within. The characters that Bastable eventually allies with strive to push against the tide of brutality... often with little success. Still, Moorcock’s message roars out at us: even though our free will is almost entirely powerless against the sweep of history, it still carries with it the possibility that through our efforts and exertions we might perhaps effect change. In this, Moorcock offers us a far more grounded hope than Wells.

Enjoyed this, Chris. Not sure you maintained the thread of "free will," but I enjoyed nonetheless. It's certainly a slippery topic that haunts me daily. I advocate for Bergson's vision in this regard: that free will is built into the evolution of the universe. But there seem to be a number of factors that push back. One of the weirdest issues that preoccupy me is the delay of our perceptions: how long is that delay? If one accepts that there are psychics who can see the future, usually up to 5 or 6 months in advance... that would imply that most of us live in a 5-6 month lag. If Einstein was right about block time, all of time is already set out. Sounds a bit like Nietzsche. Truly fascinating (and humbling) subject. Thanks for giving it a kick.